Just over ten years ago, Karl Fisch wrote a blog post that has stuck with me through the years. In it, he asked if it was OK to be a technologically illiterate teacher. Even though we’ve learned greatly in the last decade about the merits of using technology to replace teachers, I think Karl’s arguments back then are even more relevant today. In this post, I’ll explain why.

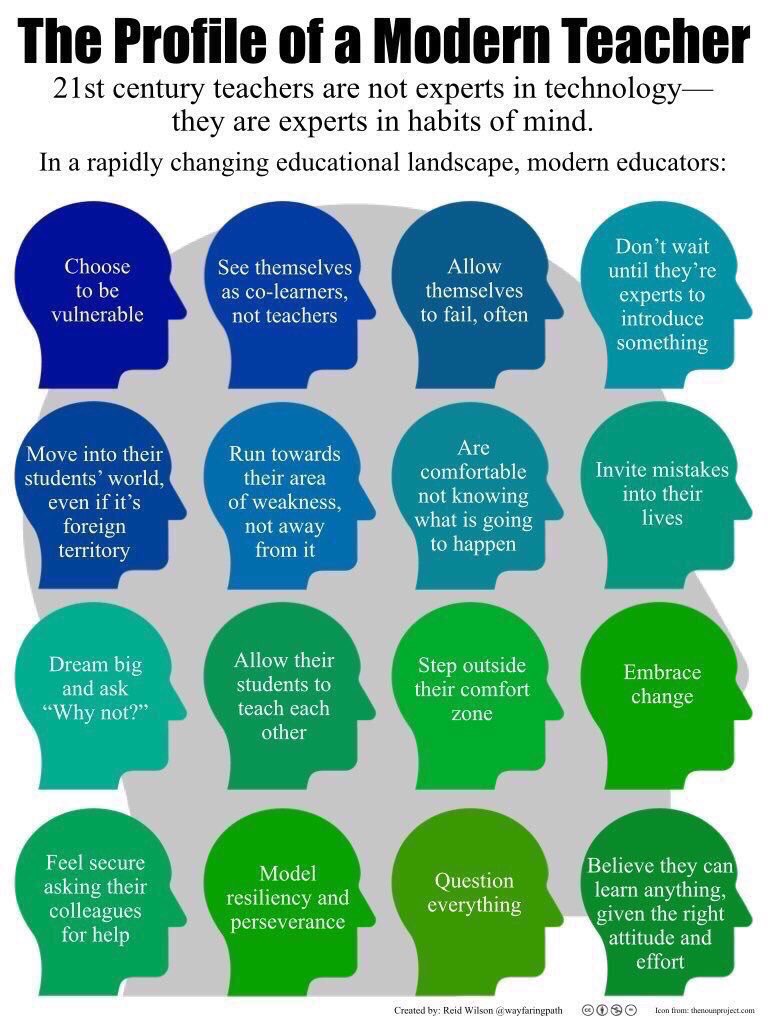

To begin, Reid Wilson created a graphic that has seen the rounds on Twitter and other networked learning channels. The graphic depicts the “profile of a modern teacher” and identifies sixteen ideal behaviors of teachers today. I’m sure you’ve seen the graphic; you probably even retweeted it.

As an educator who embraces deep learning and the innovator’s mindset, I love everything about this graphic – except its introductory statement:

21st century teachers are not experts in technology – they are experts in habits of mind.

Although perhaps Wilson didn’t mean harm when declaring that 21st century teachers need no technological expertise, to infer that today’s (public school) teachers can be successful in preparing all students for adult society, digital citizenship, and the modern workplace – without also helping them to learn how to learn with technology – misses the mark, at best, and encourages educational malpractice in today’s most severe but all-too-common circumstances.

Consider, for example, the three distinct types of technology users among youth today that Alexandra Samuel described for us last May. In her under publicized but critically important TED Ideas opinion post, Samuel illustrated the differences between digital heirs, digital orphans, and digital exiles, providing us with a “helpful lens to think about how young people are growing up with tech and what impact these formative experiences could have.” Here’s a brief summary:

- Digital Heirs – Have significant access to technology, along with the adult interaction required to learn how to use it both responsibly and powerfully. These teens have impressive tech skills, along with expectations for a society steeped in technological efficiency.

- Digital Orphans – Have significant access to technology, but lack adult guidance along the way. Who among us hasn’t seen 3-year-olds, 12-year-olds, and 17-year-olds with free and unsupervised reign on as much technology as they could ever want? Sexting and online bullying without (immediate) consequence are just the beginning.

- Digital Exiles – Have been denied access by adults to technology and digital learning networks for a myriad of good – and not-so-good – reasons. Sometimes fear lies at the heart of these restraints, and other times its cautious prudence.

Regardless of the impetus for children to live throughout childhood as digital orphans or digital exiles, the fact is that because of their lack of in-depth exposure to technology as a powerful tool for learning, they will reach young adulthood less prepared than their digital heir peers to thrive in an online and technology-dependent society. Honestly, there are only so many unplugged jobs out there.

Now consider what happens when, say, an elementary teacher in a public school classroom chooses to not use technology with her students; because she’s scared, or believes that “kids get enough screen time at home,” or has a principal that never checks his email so why should she. For that (likely relatively high) percentage of digital exiles and orphans in her class, this means an entire year of digital learning lost and/or an entire year of unsupervised misbehavior.

And no quantity of “habits of mind” expertise can really make this OK. Can it? Will modeling for these kids perseverance, vulnerability, and the value of questioning everything help them enough to fix bad technology habits already acquired, or to learn to think critically about what a balanced and collaborative life really feels like? To equitably provide today’s digital heirs, exiles, and orphans the foundation and learning they need requires a deep skill-set that not only includes expertise in habits of mind, but also in the knowledge, skills, and dispositions essential to enabling effective technology-facilitated instruction.

More than ever before, that percentage of digital orphans and digital exiles who sit in your classroom today needs caring adults who can model for them the new learning partnerships and deep learning opportunities that exist only through digital technology’s skillful and balanced use.